Background

Currently, over 65 million people are forcibly displaced worldwide, and more than 22 million are recognized as refugees. Conflicts are becoming more frequent and prolonged, which means many refugees remain in that status for over a decade.

Most funding for refugee needs comes from high-income countries (HICs) and is typically released only after emergencies happen. For example, in 2016, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) allocated around 12% of its total budget to health-related sectors like nutrition, food security, water, and sanitation.

As health demands increase and healthcare becomes more expensive—especially in middle-income countries—this reactive funding model is proving unsustainable.

Main Idea

With today’s growing number of long-term refugee crises, it’s clear that traditional funding sources are no longer enough. There is an urgent need to find new and creative ways to finance refugee health services.

This involves not just identifying fresh sources of money, but also creating flexible and effective financial tools suited to different refugee situations. The ultimate aim is to integrate refugee healthcare into the host nation’s regular health system. Done right, this benefits both local populations and refugees.

To make this shift, we need to move away from short-term crisis funding and adopt long-term, risk-based financial planning. This includes tools like health insurance, performance-based contracts, concessional loans to host governments, and even health bonds. Different financing strategies should be matched to specific refugee situations, and their possible risks carefully studied.

Conclusion

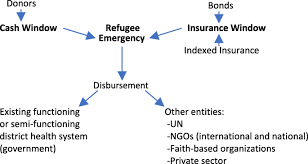

We propose developing a new Refugee Health Financing Model (FinRef) that addresses health needs during the early phase of emergencies and explores options like health insurance and pay-for-performance contracts in prolonged refugee settings.

These approaches require collaboration between traditional donors and new players, including private investors. While some models may not work in every context, they provide a way forward for more stable and efficient refugee health systems.

In-Depth Background

By the end of 2016, over 65 million people had been forcibly displaced globally, including 22.5 million refugees. Whether refugees live in camps or with host communities, and whether they are in low-income (LICs) or middle-income countries (MICs), meeting their health needs is a massive challenge. Many host countries have under-resourced health systems, which are further strained by the arrival of refugees.

The goal is to integrate refugee healthcare into national health systems wherever possible. When the host country’s system is either non-functional or overwhelmed—especially during the early phase of a crisis—temporary parallel health systems may be required.

This proposal is based on five key points:

- Refugees have a right to universal health coverage.

- The humanitarian system is overstretched and underfunded.

- Traditional emergency funding from HICs is unsustainable.

- Most funding currently comes as post-crisis aid to UN agencies and NGOs.

- Refugee crises are often long-term; the average refugee stays in displacement for over 10 years.

Different refugee contexts—such as camp vs. non-camp settings, urban vs. rural areas, and LICs vs. MICs—require tailored healthcare solutions. Ideally, host country health systems should include refugees, but where this isn’t feasible, alternative solutions like NGO-led parallel systems are used temporarily.

Emergency Risk Financing Tools

Refugee emergency financing tools have two main aspects: risk and timing.

- Risk is the possibility of loss, either individual or systemic. Risk-retention tools keep the responsibility with the host country (e.g., budget allocations, contingency funds). Risk-transfer tools shift the risk to another entity (e.g., insurance, bonds).

- Timing refers to when funds are accessed. Pre-emergency (ex ante) tools include insurance, reserves, and contingency plans. Post-emergency (ex post) tools include donations and loans after a crisis hits.

Effective planning uses a combination of these instruments, customized to each refugee context.

Traditional Humanitarian Financing

In 2016, global humanitarian aid reached $27.3 billion, mostly flowing from governments to multilateral organizations like the UN. Five major donors (mainly HICs) provided 65% of this total. Private donations also increased to $6.9 billion.

Protracted crises such as those in Syria and South Sudan absorbed more than half of the funding. However, most of this aid was given yearly instead of in multi-year packages, limiting long-term planning.

While host governments contribute financially to supporting refugees, their input is hard to quantify due to poor tracking. Most refugee funding comes from HIC donations, mainly through UNHCR, which spent $3.2 billion in 2016, with $1.9 billion going to Africa and the Middle East.

Innovative Health Financing Options

Innovative financing refers to new ways of raising and distributing money beyond traditional government-to-UN pipelines. These methods aim to access more varied sources, including the private sector, and use advanced tools tailored to specific refugee needs.

Insurance and Bonds

- Traditional Health Insurance: This involves pooling risk through premium payments, which the insurer uses to cover losses. The goal is to integrate refugees into national health insurance systems. Where systems are semi-functional, external support can help bridge the gap. This approach requires that refugees have the right to work so they can afford premiums.

- Community-Based and Microinsurance: These small-scale, locally-managed schemes target poor and excluded populations. They require community trust and consistent contributions. Though not yet widely applied to refugees, CBHI schemes have potential in stable, long-term refugee settings.

- Catastrophe Bonds and Indexed Insurance (FinRef Model): These tools are tied to specific events like natural disasters or refugee influxes. For example, bonds may not be repaid to investors if a disaster occurs, and the money is used instead for emergency response. FinRef aims to use such bonds and insurance to pre-fund refugee health responses. Indexes could include the number of refugees crossing borders or a country’s fragility score.

Grants and Loans to Host Governments

In 2016, the World Bank launched a $2 billion facility to help refugee-hosting LICs. MICs have access to the Global Concessional Financing Facility (GCFF), which offers long-term, low-interest loans. These funds encourage governments to develop inclusive health strategies for both nationals and refugees.

Many long-standing refugee camps still rely on separate health services. While these have often produced better outcomes than host systems, they are not sustainable. The goal is to redirect funding from parallel systems to improve national health infrastructure, benefiting both communities.

Remittances

Refugees often pay out-of-pocket for health services, especially in urban settings. They rely on informal work, loans, or remittances from relatives abroad. Remittances globally surpass $441 billion annually and are proven to support health, education, and small businesses.

Though remittances are helpful, they should not replace health financing. Policies should aim to reduce transfer fees and support easier money flows in refugee settings.

Pay for Performance (P4P)

P4P is a method where private investors fund health programs upfront and are repaid only if specific goals are met. While this model is complex and data-intensive, it can work well for measurable interventions in refugee camps—like increasing vaccination rates or reducing malaria deaths.

P4P is most suitable for long-term, stable refugee settings and should not be used during the early stages of emergencies when broad health system strengthening is needed.

Final Thoughts

With increasing numbers of long-term refugees and rising healthcare demands, traditional funding approaches are no longer enough. By borrowing ideas from development financing and customizing them to refugee needs, we can unlock more funding and make better use of current resources.

Partnerships among governments, private investors, UN agencies, and NGOs will be essential. Multiple innovative financing models should be tested and adapted to different refugee situations. While not all will succeed, those that do can provide sustainable, high-quality healthcare for refugees and host populations alike.

Join Gen Z New WhatsApp Channel To Stay Updated On time https://whatsapp.com/channel/0029VaWT5gSGufImU8R0DO30